Imagine you are slowly piling up notifications on your phone. A friend texts you, a teacher posts a new assignment, a group chat explodes with memes, your bank app pings you about a payment. For a while, you handle everything with a few quick taps. Then one more message lands at precisely the wrong moment, and suddenly you miss a deadline, forget a meeting, and end up in a mini-crisis. From the outside, a slight extra nudge has caused a surprisingly big mess. This feeling that “nothing much changed, but suddenly everything tipped over” is at the heart of what Bak and colleagues call self-organized criticality.

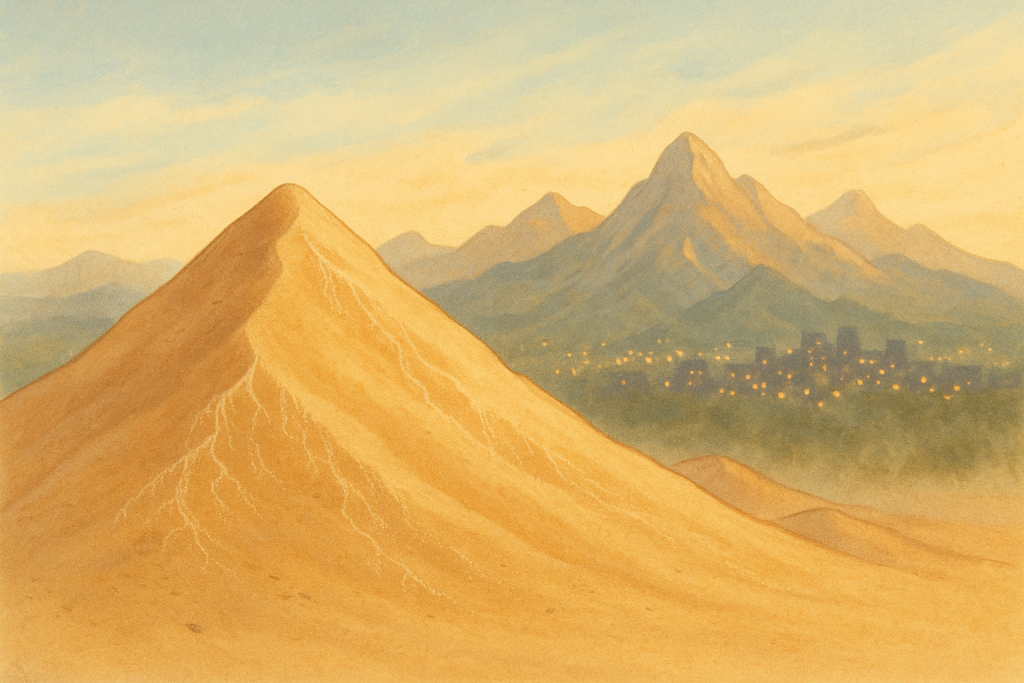

According to Bak et al., many large systems in nature and society slowly move toward a special state where they are just barely stable. To explain it, they use a simple picture: a pile of sand. Grain by grain, the pile grows steeper. Most grains fall to the ground and do almost nothing. But sometimes a single grain makes a small slide, and sometimes it sets off an enormous avalanche that runs all the way down the side. The rules that describe this sandpile are straightforward, yet the result is remarkable: the pile naturally settles into a state where avalanches of all sizes occur. There is no single “typical” size or time. The same idea can be applied to many systems that change incrementally, such as the flow of rivers, the light from distant quasars, the Sun’s activity, and even the movement of prices on a stock market.

Bak and colleagues demonstrate that in this special state, small causes can have effects on multiple scales. This is why they discuss “1/f noise,” also known as flicker noise. Instead of random, short blips, the system displays slow, long-lasting fluctuations alongside quick ones. If you think of your life, you can picture days where nothing much happens and then a period where many things change at once: a new job, a new city, and new people. In their models, this occurs because the system is constantly balancing on the edge between calm and collapse. Energy, pressure, or “slope” builds up everywhere, and then it is released in bursts that can be tiny or huge. The pattern in space also looks special: instead of neat, regular shapes, you get messy, repeating patterns that look similar at different scales, like mountain ranges or coastlines.

The most striking message of Bak et al. for everyday life is that constant small changes can quietly push systems toward a critical point. A friendship, an online community, or even your own schedule can become a “sand pile” where tension slowly builds up. One more careless comment, one more late night, or one more task added to your to-do list may then trigger an “avalanche” of reactions. This does not mean that everything is always on the verge of falling apart. It means that in many real situations, there is no single obvious warning sign or simple knob you can turn to avoid all problems. Instead, it helps to notice how often you are adding “grains of sand” to your life without giving the system time to relax. Taking breaks, solving minor conflicts early, and not letting every part of your day reach its limit is like gently smoothing the sand pile before it gets too steep. Understanding self-organized criticality is a reminder that significant changes often emerge from many small steps, and that paying attention to these steps is one of the most practical skills you can develop.

Reference:

Bak, P., Tang, C., & Wiesenfeld, K. (1987). Self-organized criticality: An explanation of the 1/f noise. Physical Review Letters, 59(4), 381–384. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.381

Privacy Notice & Disclaimer:

This blog provides simplified educational science content, created with the assistance of both humans and AI. It may omit technical details, is provided “as is,” and does not collect personal data beyond basic anonymous analytics. For full details, please see our Privacy Notice and Disclaimer. Read About This Blog & Attribution Note for AI-Generated Content to know more about this blog project.