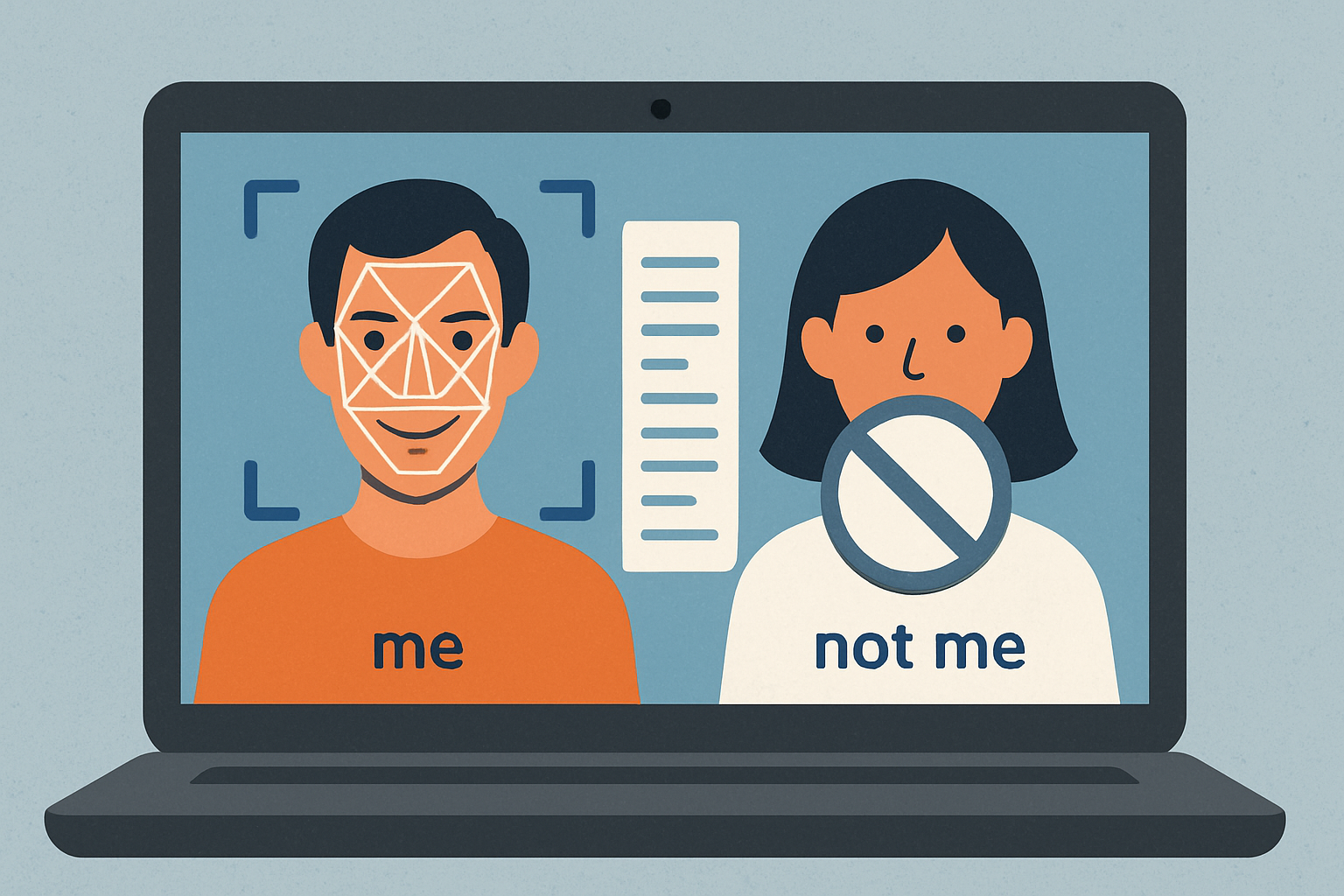

You open your laptop, and a familiar app feels off. It launches slower. A button is gone. Is it just a glitch, or did something actually change? Forrest and colleagues suggest a simple way to think about this: teach the computer what “self” looks like, then watch for anything that isn’t “self.” Their idea borrows from the immune system, turning change detection into a game of “spot the difference.” Instead of chasing every known virus pattern, the system learns your files when they’re clean and flags anything that doesn’t match that clean picture.

Here’s how it works, in everyday terms. Take a file you want to protect and slice it into many small pieces, like cutting a playlist into short clips. Then generate lots of random “detectors,” but immediately throw away any detector that looks too much like your file pieces. That pruning step is called “censoring.” What’s left is a customized set of detectors that match almost anything except your file. Later, the computer regularly compares your file pieces to those detectors; if one suddenly matches, something changed, and you get an alert. The matching rule is flexible: it doesn’t need a perfect match, only a few symbols in a row, which makes it sensitive to real edits. This approach is best suited for items that shouldn’t change often, and it won’t detect pure deletions, which is a known limitation.

The clever twist is probability. Each computer (or app) builds a unique detector set, so even if an attacker slips past one, the same trick is likely to fail elsewhere. System-wide reliability ends up high, even if any single spot is only “pretty good.” You can tune how cautious the system is: more detectors cost more to prepare but provide stronger protection, while day-to-day checking remains inexpensive. Experiments in the paper demonstrate the idea’s ability to catch everything from minor edits to simple file-infecting viruses, and detection improves rapidly when multiple independent copies are involved. Protection is also symmetric: if someone tries to tamper with the detectors themselves, the same checking process detects that change as well.

What does this mean for your daily life? Think of it as a mindset: know your “self,” then watch for drift. When you install software or store important notes, taking a clean snapshot and checking against it later can reveal sneaky changes early. You can also spread the checking across multiple locations—such as a laptop, cloud copy, or external drive—to achieve that system-level boost from diversity. The authors are honest about trade-offs: generating a strong detector set can be computationally intensive, and attackers could try tricks like reusing their own pieces, so varying how you slice things raises the bar. The bottom line is motivating: by learning “me” first and automating the “is this still me?” question, you gain a practical, immune-inspired way to keep your digital content trustworthy without getting bogged down in technical jargon.

Reference:

Forrest, S., Perelson, A. S., Allen, L., & Cherukuri, R. (1994). Self-nonself discrimination in a computer. Proceedings of 1994 IEEE Computer Society Symposium on Research in Security and Privacy, 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1109/RISP.1994.296580

Privacy Notice & Disclaimer:

This blog provides simplified educational science content, created with the assistance of both humans and AI. It may omit technical details, is provided “as is,” and does not collect personal data beyond basic anonymous analytics. For full details, please see our Privacy Notice and Disclaimer. Read About This Blog & Attribution Note for AI-Generated Content to know more about this blog project.