You’re juggling classes, a part-time job, and maybe a side hustle. Every week brings a new app to try, a study trick to test, and a different way your friends are making money online. It can feel like the world keeps changing just when you think you’ve figured it out. Holland and Miller describe this kind of world as one that’s always throwing something new at us, where smart choices come from adapting step by step rather than guessing the perfect plan in advance. In their view, useful patterns can be tested inside “artificial worlds,” like simulations, so we can watch how strategies improve over time and see which ones actually work.

According to Holland and Miller, many real-life settings look like “complex adaptive systems.” Think of a campus or a marketplace: lots of people trying things, learning from feedback, and adjusting based on what everyone else does. There isn’t one final, perfect strategy; instead, you find local “niches” where certain habits pay off—like a study routine that works for your schedule or a pricing trick that fits your small shop. New moves by others create new niches, so improvement never really stops—more like constantly upgrading your loadout in a game than finishing a final boss.

So how do you get better inside a shifting system? One idea is to learn the way a basic “genetic algorithm” learns: keep a bunch of simple strategies, reward the ones that perform well, and mix their best parts to create new ones. In plain terms, if Pomodoro sprints help you focus and walking meetings spark ideas, combine them into “walk, then sprint” and test again. This mixing step—called “crossover”—is powerful because it builds on what already works, instead of starting from scratch each time. Over many rounds, you bias your search toward better “building blocks,” and your average results rise without you needing perfect information or heavy math.

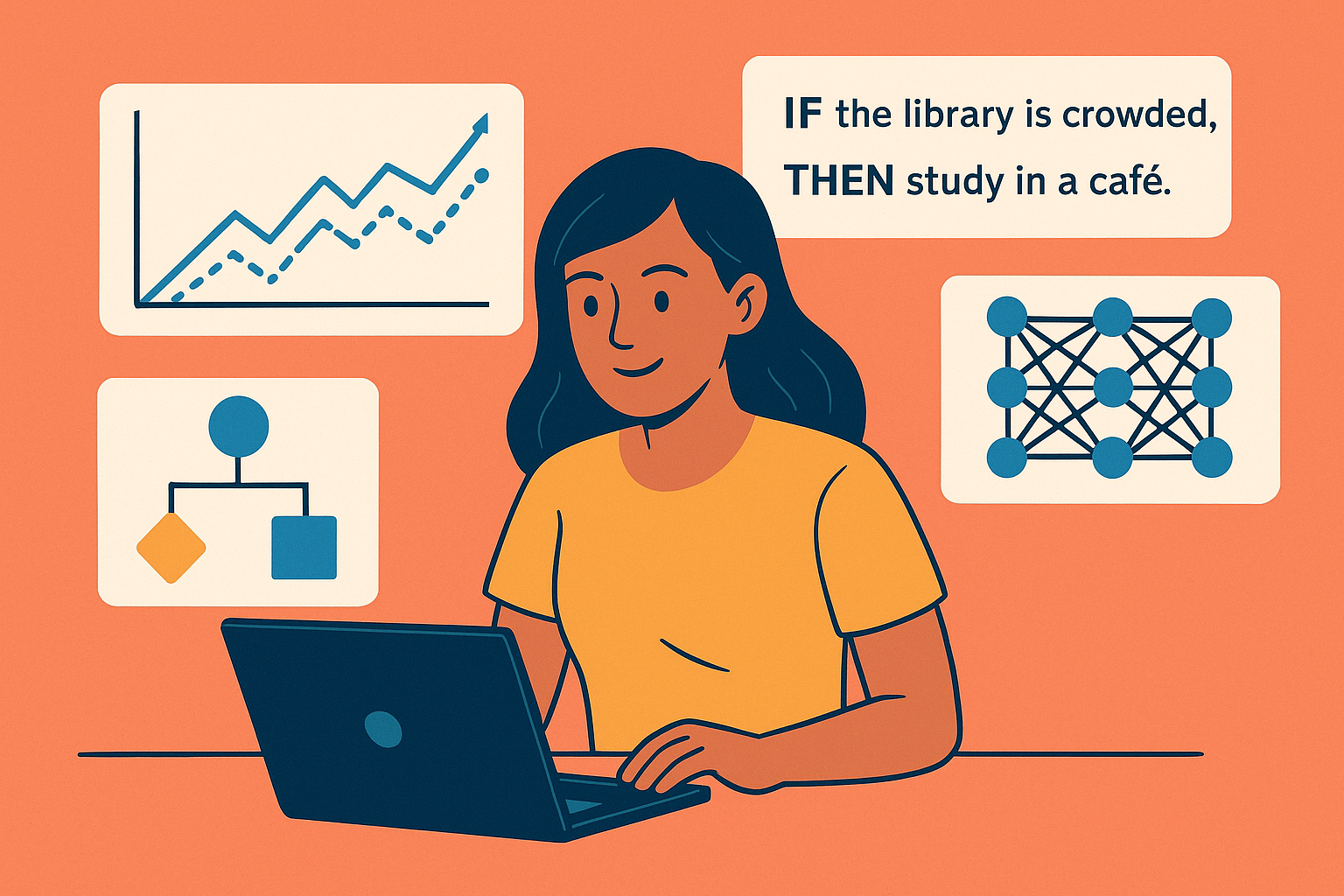

Another tool they discuss is a “classifier system,” which you can picture as a bunch of if-then rules competing to guide your next move: if the library is crowded, then study in a quiet café; if a post flops, then try a shorter caption. Each rule earns “strength” when it helps you get a payoff and loses strength when it doesn’t—like a built-in scoreboard for your habits. Over time, helpful rules link up, forming smarter routines that still stay flexible, because every rule is provisional and can be replaced when the world changes. This way of learning—small rules, constant feedback, and recombining what works—makes progress feel doable even when wins are rare or delayed. It’s a reminder that you don’t need to be all-knowing to act more intelligently tomorrow than you did today.

Reference:

Holland, J. H., & Miller, J. H. (1991). Artificial Adaptive Agents in Economic Theory. The American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings of the Hundred and Third Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, 81(2), 365–370. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2006886

Privacy Notice & Disclaimer:

This blog provides simplified educational science content, created with the assistance of both humans and AI. It may omit technical details, is provided “as is,” and does not collect personal data beyond basic anonymous analytics. For full details, please see our Privacy Notice and Disclaimer. Read About This Blog & Attribution Note for AI-Generated Content to know more about this blog project.